Foreword

From 1775 to today, the Army JAG Corps has built a legacy of legal excellence in support of our Army and our Nation. The history of our Corps is filled with incredible stories of Soldiers demonstrating heroism, character, and brilliance in the execution of their duties. Over the past 250 years, the JAG Corps has shared many challenges with our Army and with our Nation. Through it all, the four constants of our dual profession—principled counsel, mastery of the law, servant leadership, and stewardship—have been foundational to our practice, while our history demonstrates that change is a fifth constant.

The JAG Corps of 2025 operates in a complex, dynamic, and uncertain environment. In a time of shifting geopolitics and unprecedented technological advancement, the Army has been called on to "transform in contact." This effort will require the JAG Corps to embrace change as we continue supporting our individual clients and our Army. Even as things change, many continuities in our practice will remain. We will protect fairness and due process while maintaining our Army's critical expeditionary justice capabilities. We will ensure that our Army is prepared to compete and prevail across the spectrum from competition to conflict, steadfastly upholding the rule of law. We will continue to be charged with engaging in the Nation's most consequential practice of law.

As we consider the demands of the twenty-first century, a look back on our history gives us much-needed perspective on the challenges we face on a daily basis. We can take inspiration from understanding where we have come from and what our predecessors have achieved. Their examples should motivate each of us to strive to be the best that we can be for our Corps, our Army, and our Nation.

The U.S. Army JAG Corps - A History

A Legacy of Legal Excellence

Origins

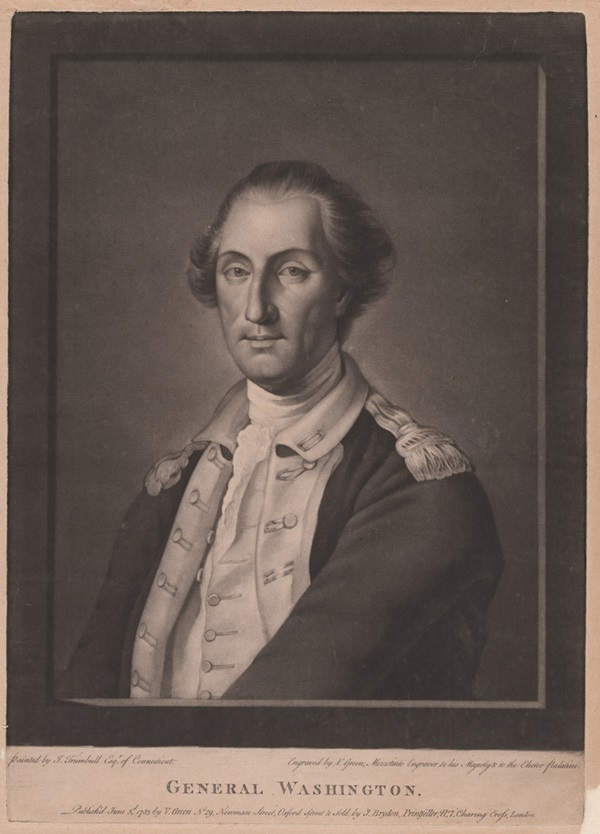

On July 29, 1757, Colonel George Washington of the Virginia militia wrote that “Discipline is the soul of an army. It makes small numbers formidable; procures success to the weak and esteem to all.” With the outbreak of the American Revolution in 1775, Washington found himself in charge of a motley assemblage of militiamen from different colonies. Washington recognized that for both military effectiveness and to gain legitimacy in the eyes of the European powers—and ultimately aid for the American cause—the American army had to be trained and disciplined to fight like a professional European force. An essential aspect of this project was an effective system of military justice.

The First Judge Advocate General

At Washington’s request, Congress appointed William Tudor to serve as Judge Advocate of the Army with the rank of lieutenant colonel. Tudor had clerked and studied law under John Adams prior to beginning his own practice in Massachusetts. In 1776, Tudor’s title was updated to Judge Advocate General. Tudor’s tenure was relatively brief, ending in April 1778.

Tudor's Successors

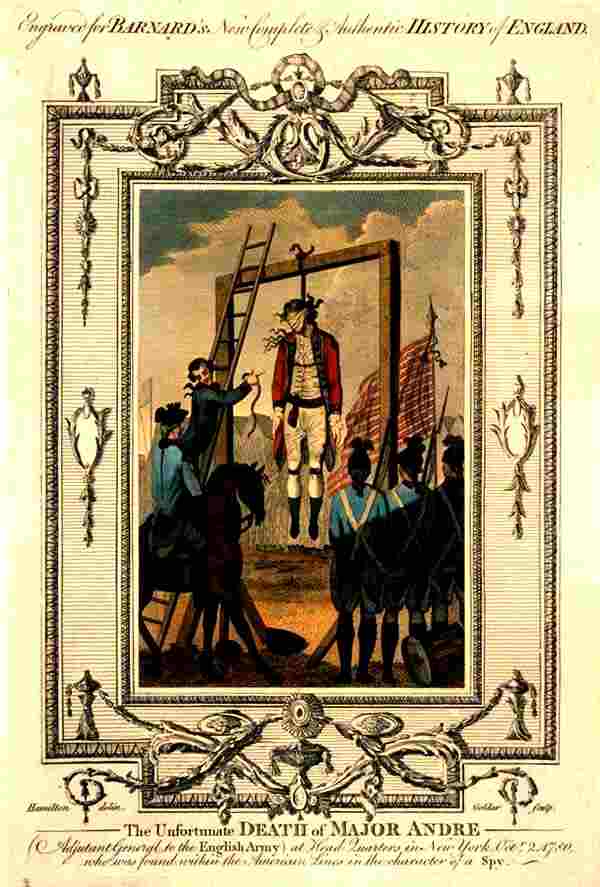

Two other men, John Laurance and Thomas Edwards, would subsequently serve as Washington’s judge advocate general during the war. Laurance prosecuted or presided over several well-known cases: the court-martial of Charles Lee for insubordination (1778), the court-martial of Benedict Arnold for misconduct (1779), and the espionage case of British officer Major John André (1780).

Antebellum Period

The most significant development in the antebellum period was Congress’ passage in 1806 of the Articles of War, rules and regulations for the Army that would remain in effect (with revisions) until 1951.

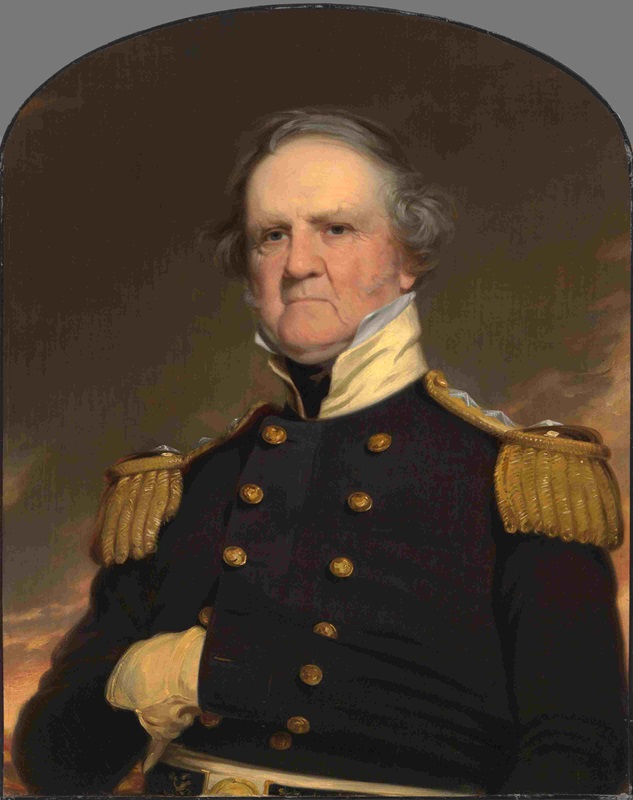

Judge Advocates Before the Civil War

From the conclusion of the American Revolution until the Civil War, the American Regular Army and its legal practice remained small. After Captain Campbell Smith served intermittently from 1794 to 1802 in a position equivalent to the Judge Advocate General, Congress abolished the position and made no provision for full-time judge advocates until the War of 1812. Once again, between 1821 and 1849 Congress made no provision for a full-time judge advocate for the Army. Instead, line officers were expected to serve as judge advocates as an additional duty when a court-martial was convened. General Winfield Scott was a member of Virginia bar and had served as a judge advocate. In 1847, he established a system of military tribunals to prosecute Mexicans and American troops in occupied areas of Mexico for conduct not triable by courts-martial under the then-existing Articles of War.

The Civil War Era

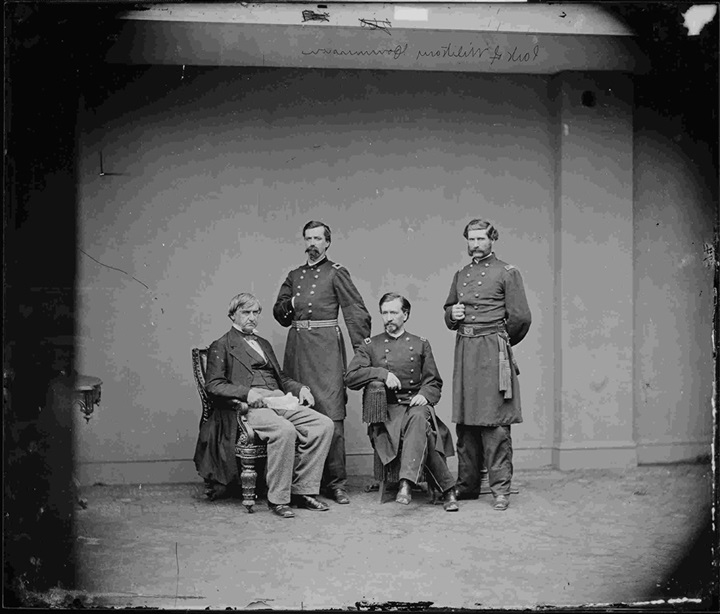

The trajectory of what would become the Army JAG Corps was dramatically affected by the outbreak of the American Civil War. On September 3, 1862, concerned over Judge Advocate of the Army John Fitzhugh Lee’s apparently weak commitment to the Union war effort, Congress superseded his position and created a new one – Judge Advocate General – for Joseph Holt.

The Civil War once again saw a temporary expansion in the number of judge advocates serving in the Army. More importantly, it had lasting impacts in the areas of military justice, the law of domestic operations, and the establishment of a permanent organization to provide legal support to the Army. This last development was marked by the creation of the Bureau of Military Justice in 1864 and the elevation of the Judge Advocate General billet to a brigadier generalship.

The Lieber Code

Perhaps the best-known change to military justice during the Civil War was the 1863 promulgation of General Orders No. 100, also known as the “Lieber Code,” as an addendum to the Articles of War. Authored by legal scholar Francis Lieber, the Army for the first time incorporated common law crimes under the Articles of War as well as defining what would today be called the law of armed conflict. Judge advocates would be charged with enforcing the new regulations. Eventually, this innovation would influence the creation of a body of international law at the Hague conventions of 1899 and 1907. The Civil War years would also see the implementation of the first form of appellate review, with the Judge Advocate General reviewing all court-martial or military commission sentences of death or a penitentiary term prior to Presidential review.

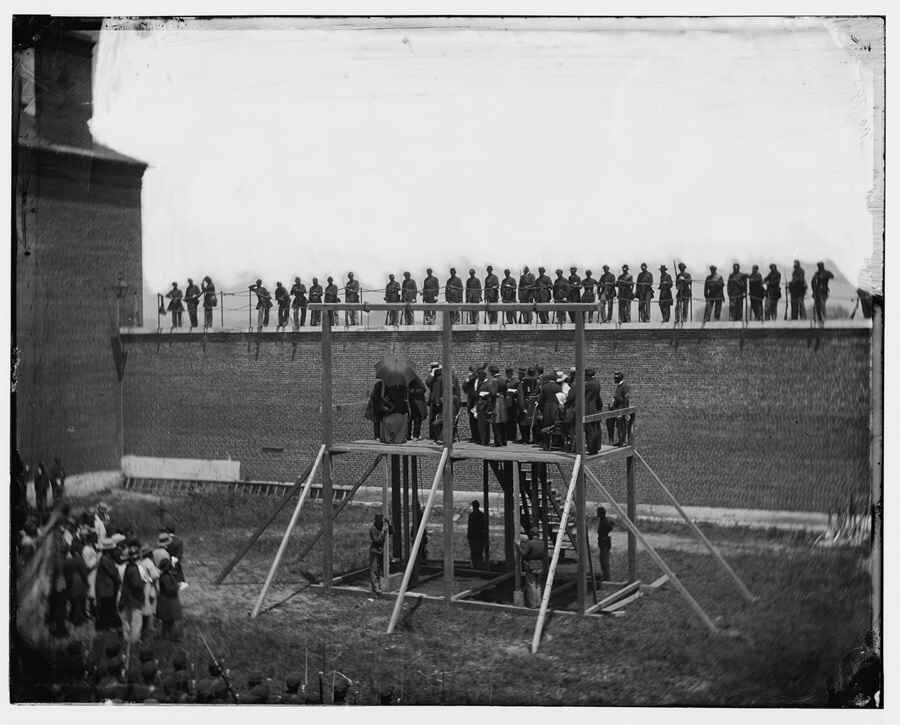

A Nation in Arms

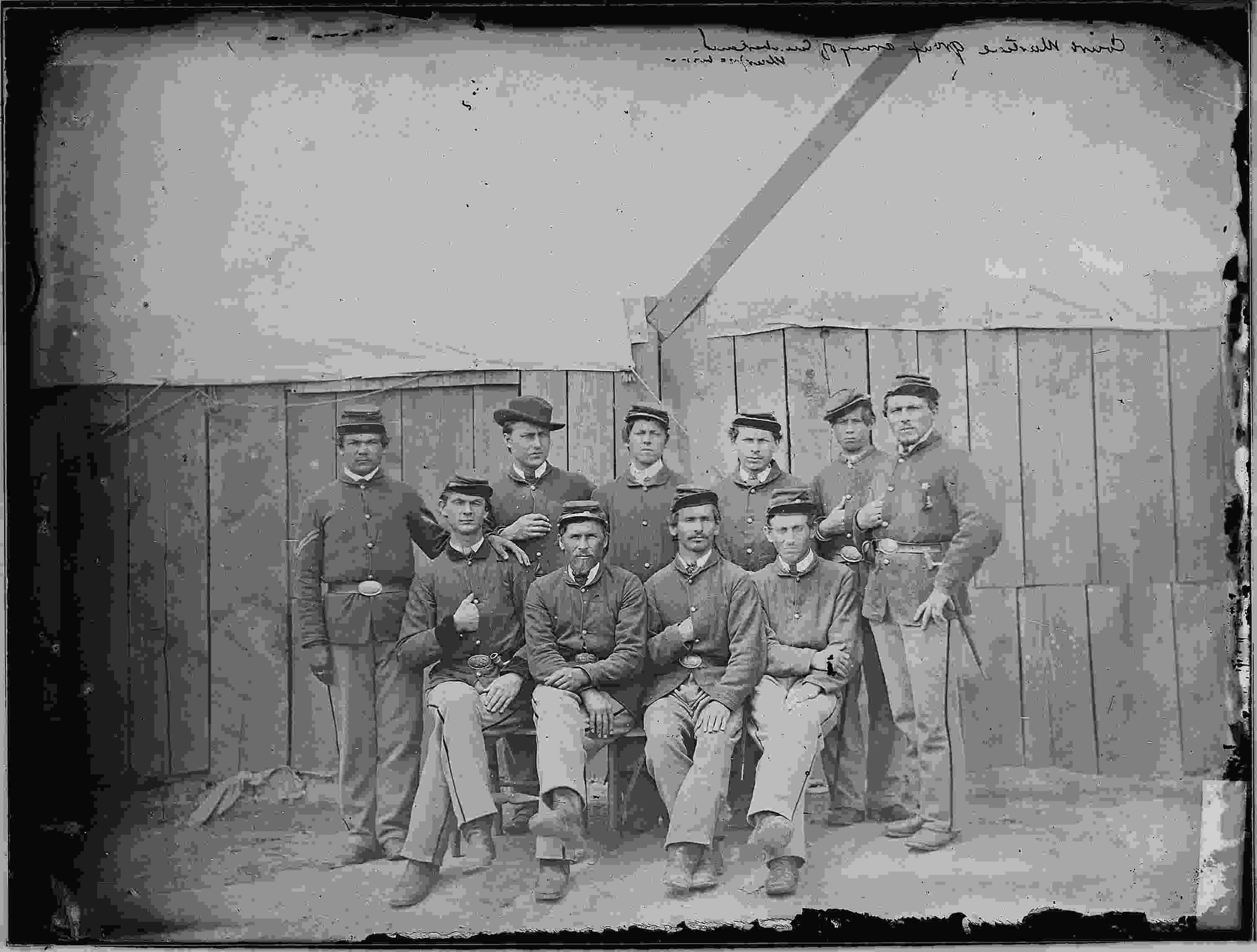

Because the Civil War was fought on domestic soil, it created important legal precedents regarding the use of martial law and military commissions. Joseph Holt strongly supported Lincoln’s suspension of habeas corpus and prosecution of civilians by military courts. Holt personally prosecuted former Andersonville prison camp commandant Henry Wirz and the Lincoln assassination conspirators at military commissions run by the Army. In contrast to Holt’s aggressive use of the military against civilian defendants, the Supreme Court handed down the Ex parte Milligan rulings in 1866, finding that non-military citizens could not be “tried, convicted, or sentenced otherwise than by the ordinary courts of law” in a jurisdiction so long as the civilian courts were open and operating. The Milligan decision has undergirded the Army’s approach to domestic operations ever since.

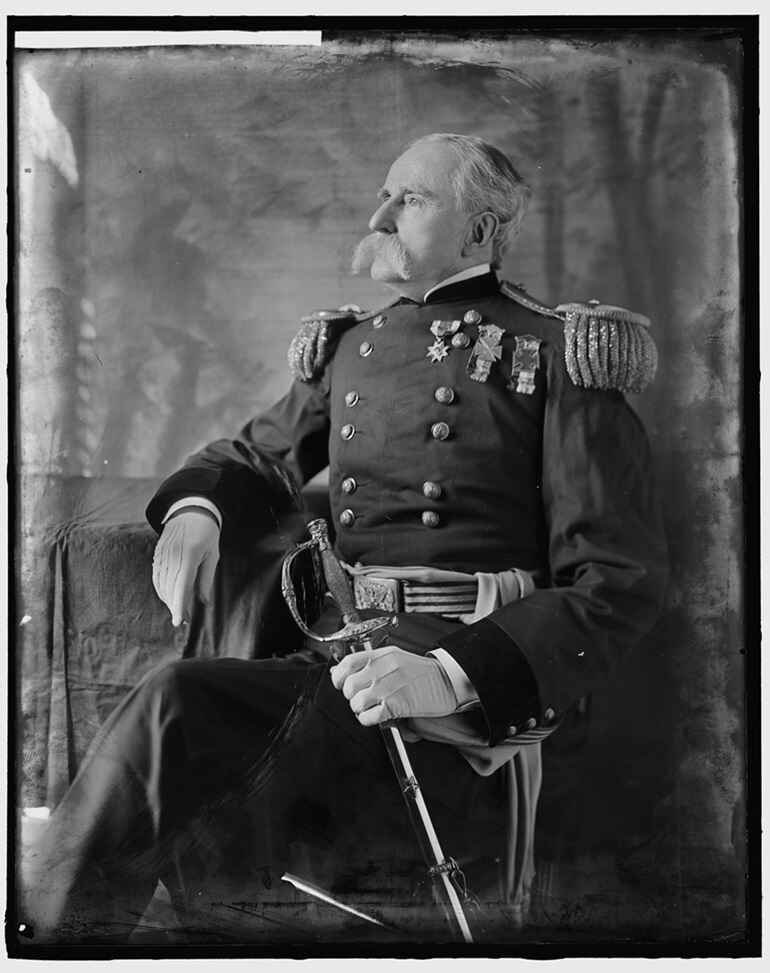

The JAG Department before the World Wars

With the end of the Civil War came another drawdown in forces as the Army returned to its primary role as a frontier constabulary. This time, however, the Bureau of Military Justice and the position of Judge Advocate General remained in place. The Army’s legal practice was renamed the Judge Advocate General’s Department in 1884. It would retain this title until 1949. For the JAG Department, the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries were a period marked by legal scholarship and incremental reform. Brigadier General Guido Norman Lieber, son of Francis Lieber, lead the Judge Advocate General’s Department for 16 years. Lieber is best known as the author of several influential treatises on military law, including The Use of the Army in Aid of the Civil Power (1898) and Remarks on the Army Regulations (1898). As the Spanish-American War began in 1898, Lieber published and distributed a pocket edition of General Orders No. 100. The Army published the first edition of A Manual for Courts-Martial in 1895. A few years prior, in 1890, the Articles of War had been amended to eliminate sentencing “left to the discretion of the court-martial.” Where before there had been no statutory maximum punishment for any crime, excepting limitations on the death penalty, the President would now prescribe maximum sentences, which were duly promulgated by executive order in 1891. Although the reforms of the time were relatively minor, the Progressive era JAG Department saw the initiation of the increasing conformity of military law with civilian legal practices by custom, regulation, and statute.

The First World War

While the JAG Department and the rest of the Army was undergoing a process of modernization and professionalization around the turn of the twentieth century, the United States’ entry into the First World War in 1917 sowed the seeds for even more dramatic changes to come. With a prewar strength of 108,000 personnel, including a total of 32 Army lawyers in the JAG Department in 1916, the Army would have to undergo a massive and rapid mobilization to deploy combat effective forces to the Western Front. By 1918, the Army’s strength stood at nearly 2.4 million Soldiers, mostly raised through conscription. The first major change for the JAG Department resulting from the Army’s rapid growth was not only more positions for judge advocates, but also the formal assignment of enlisted personnel for the first time. While this was a temporary development, it marked a departure from the traditional practice of detailing enlisted personnel from other specialties to serve as court reporters and legal clerks.

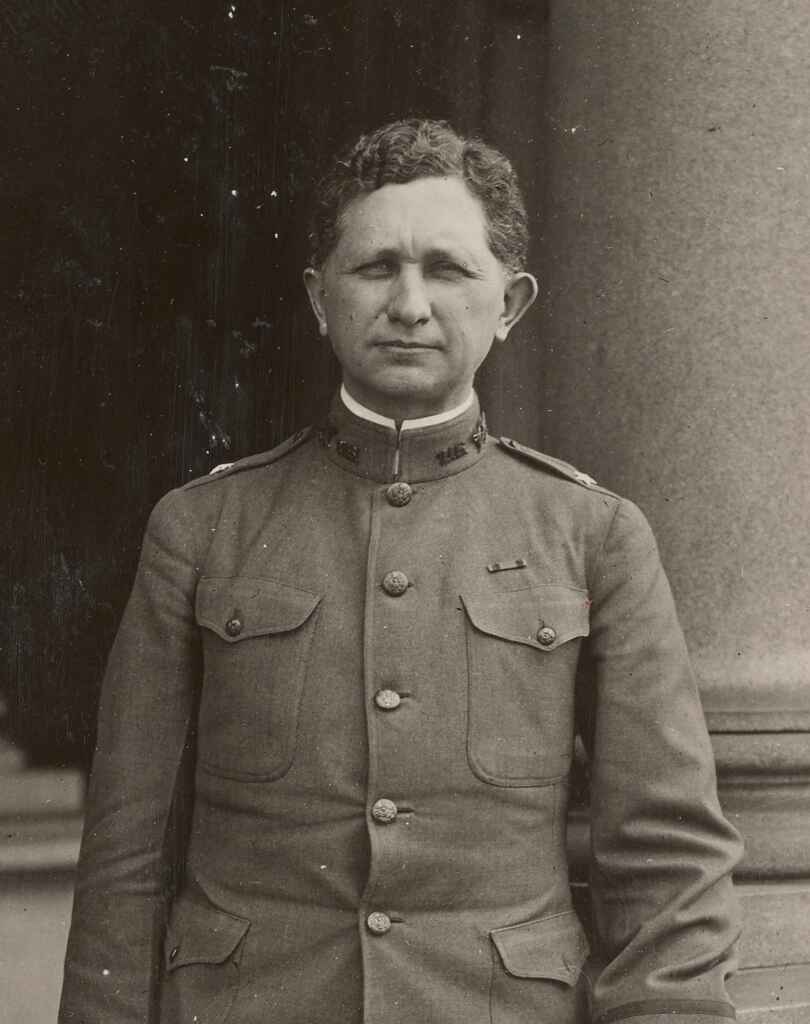

The Ansell-Crowder Controversy

The second major development for the JAG Department centered around what was known as the Ansell-Crowder controversy. In 1917, Judge Advocate General (tJAG) Enoch Crowder was serving as the Provost Marshal General for the Army, leaving acting Judge Advocate General Samuel Ansell to run the JAG Department. Ansell interpreted an 1878 statute as giving him the authority to set aside the findings and sentences in court-martial cases. Crowder learned of Ansell’s intentions in a mutiny case from Fort Bliss and disagreed, informing the Secretary of War that Ansell’s interpretation of the statute was wrong.

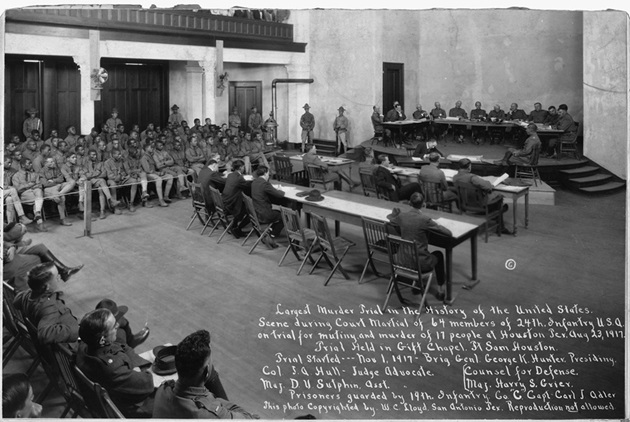

Ansell's Legacy

Their disagreement continued in the aftermath of the Houston Riot cases, when thirteen Soldiers of the African American 24th Infantry Regiment were executed only two days after their sentencing for their alleged participation in a mutinous riot spurred by rumors of police abuse of a fellow Soldier. Ansell strenuously objected to the lack of opportunity for clemency and again insisted on his right to review courts-martial sentences. Additional cases of harsh punishment with little due process in the American Expeditionary Forces in France only heightened Ansell’s concerns over the state of military justice. Ansell proposed a litany of reforms, including a system of appellate review; the clarification of punitive offenses in the Articles of War; statutory penalties for punitive offenses; mandatory preliminary investigation prior to referral to court-martial, to be reviewed and approved by a judge advocate; the inclusion of enlisted personnel on courts-martial panels; and the creation of a judicial position in courts-martial. Crowder publicly disagreed with Ansell’s opinions and recommendations, arguing that courts-martial were not courts in the civilian sense, and that the military justice system existed purely to enforce a commander’s disciplinary prerogative. Samuel Ansell’s real legacy lay in identifying issues with the Articles of War and making the case for military justice as an instrument of criminal justice, rather than simply as a tool for enforcing discipline. Much of what Ansell argued for would eventually be incorporated decades later into the Uniform Code of Military Justice (UCMJ).

The Second World War

With the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, the United States once again entered a worldwide conflict that was already underway. This time the American economy and military underwent a mobilization of even greater size and duration, with Army strength rising to more than 8 million Soldiers by 1945. During the war the Armed Forces as a whole would carry out approximately 1.7 million courts-martial, accounting for one-third of all court cases under American jurisprudence at the time. The JAG Department would grow from around 400 to more than 2,000 personnel over the same period. To support the requirements of military justice and growth of the Army’s legal corps, the JAG Department realized that it could not rely upon on-the-job training for the civilian lawyers now drawn into its ranks. For the first time, the Army established a JAG School to train Army lawyers. Located at the University of Michigan between 1942 and 1946, the JAG School combined an Officer Candidate School with a school for already-commissioned judge advocates. By June 1944, two-thirds of the JAG Department’s active-duty strength had been trained at the Michigan campus. Legal support to the Army during the war once again required the formal assignment of enlisted personnel to the JAG Department, and women began to serve as judge advocates in 1944.

The JAG Corps Expands

The vast scope of the Second World War saw the expansion of the JAG Department into many fields outside its traditional focus on military justice, such as claims, contracts, patents, and real estate. The Army also began in 1943 to provide legal aid to Soldiers for the first time, the beginning of the Legal Assistance program.

Pursuing Justice After the War

Perhaps most notably, the war’s aftermath saw Army legal personnel directly involved in the prosecution of war crimes. At trials in Germany, Italy, and the Philippines between 1945 and 1948, Army lawyers and legal personnel helped to prosecute and defend hundreds of former enemy officials, military personnel, and civilians charged with violations of the laws of war. Proceedings at the former Nazi prison camp at Dachau, for example, saw 1,672 individuals tried in 489 cases, resulting in a 73 percent conviction rate. While some sentences were later overturned due to the pressures of Cold War politics and, in a few cases, for misconduct by investigators and prosecutors, the JAG Department played a key role in establishing a precedent for accountability for those who violate international humanitarian law.

Military Justice Reform

Besides expanding the ranks and scope of the Army’s legal profession, the major outcome of the Second World War for the JAG Department was a renewed push for military justice reform. Many veterans complained to members of Congress of defects in the Articles of War: undue command influence over cases, wildly varying sentences for similar offenses, seeming favoritism toward officers, and more. As part of the Selective Service Act of 1948, Congress made major changes to the Articles of War, such as including enlisted Soldiers and warrant officers on court-martial panels and prohibiting unlawful command influence. This legislation also transformed the JAG Department into the JAG Corps, effective the following year. Also known as the Elston Act for its chief sponsor, the 1948 legislation only dealt with the Army’s Articles of War. With the Army, Navy, and newly independent Air Force now unified under the auspices of the Department of Defense, the Elston Act was soon superseded by the need for a comprehensive Uniform Code of Military Justice (UCMJ). On May 5, 1950, Congress passed the UCMJ. Among other significant reforms to military justice, it required “a thorough and impartial” pretrial investigation; provided the right to legally qualified counsel for the accused at general and special courts-martial; created a quasi-judicial “law officer” position; and created a three-member civilian Court of Military Appeals atop the military appellate structure. Foreshadowing a trend toward “civilianization” in military justice, Article 36 of the UCMJ stated that courts-martial should “apply the principles of law and rules of evidence generally recognized in the trial of criminal cases in the [United States] district courts.”

The JAG School

The UCMJ took effect in 1951, during the Korean War. Even before the outbreak of fighting on the Korean Peninsula, it had become obvious that the United States was going to be locked into a global Cold War with the Soviet Union and its allies and proxies. Unlike after previous conflicts, the Army would not shrink back to its tiny prewar state. The war in Korea only reinforced the need to train and maintain a JAG Corps to support a permanently enlarged Army. The JAG School was restarted at Fort Myer, Virginia, in 1950 to accommodate the wartime surge in legal support requirements. The following year it moved to Charlottesville, Virginia, where it was collocated with the University of Virginia’s law school. This time the school, known as The Judge Advocate General’s School, Army (TJAGSA), would not shut down with the termination of fighting in Korea in 1953. Moving into its own facility in 1975, TJAGSA—now known as The Judge Advocate General’s Legal Center and School (TJAGLCS) —remains on the UVA North Grounds campus.

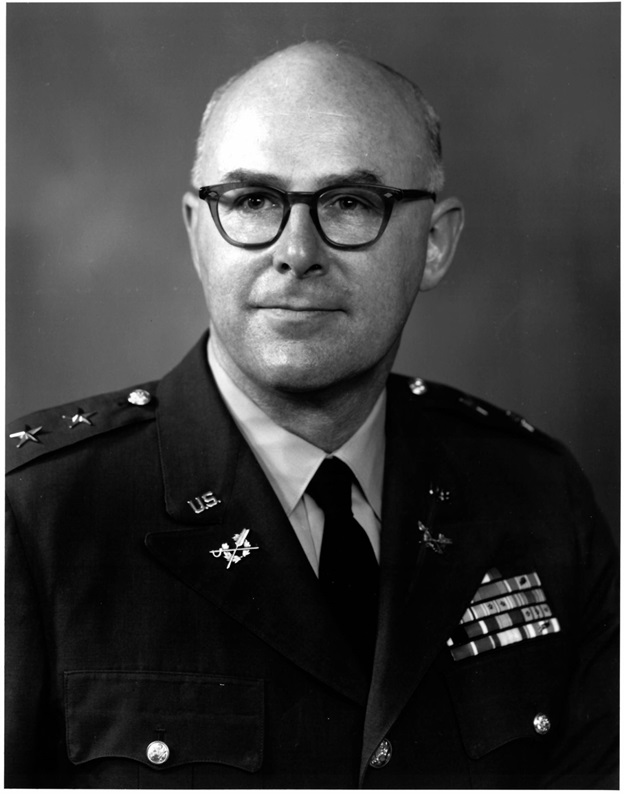

The Military Justice Act

By the mid-1960s, the Army was fully engaged in an escalating conflict in South Vietnam. The time had also come for new reforms to the UCMJ, with The Judge Advocate General (TJAG), Major General Kenneth J. Hodson, serving as a principal architect for change. The resulting Military Justice Act (MJA) of 1968 was the first major amendment to the UCMJ. The new legislation would have a major impact on the structure, composition, and training of the JAG Corps.

Legacy of the Military Justice Act

The two most important changes implemented by the MJA of 1968 were the creation of an independent military judiciary and the right to representation by a judge advocate at special courts-martial. With nearly 60,000 special courts-martial in 1969 alone, demand increased for judge advocates. Likewise, a heavier caseload made enlisted support more critical than ever. Prior to the late 1960s, the Army had trained its legal clerks first via on-the-job training and then by correspondence course. Recognizing the need to properly train these personnel, the Army created MOS 71D, legal clerk, in the late 1960s and began formally training enlisted legal personnel. Similarly, warrant officers had served in the JAG Department as early as 1928. By the 1960s, one MOS 713A, Legal Administrative Technician warrant officer, was authorized at each headquarters exercising general courts-martial jurisdiction. Like for enlisted legal personnel, the Army finally began formal training for its legal administrators during the Vietnam era, with the first classes taking place in the 1969–1970 timeframe. The creation of a military judiciary was the second major legacy of the MJA of 1968. Army judges would also assume powers previously held by the court-martial panel, such as deciding challenges for cause against panel members. For the first time, individuals facing a court-martial could request a judge-only trial, with findings and sentences decided solely by the judge. Finally, the existing Boards of Review were redesignated as Courts of Review composed of Army judges, and opportunities to appeal a conviction were expanded in scope and duration.

A New Path for the JAG Corps

By the Vietnam War era, Army lawyers were expected to primarily work in military justice, claims, civil and administrative law, and legal assistance. The concept of legal support to operations at the time basically consisted of doing the same garrison legal tasks while deployed forward, but legal personnel serving in Vietnam found new ways to support the Army. For instance, the staff judge advocate for U.S. Military Assistance Command, Vietnam, then-Colonel George S. Prugh, played a key role in convincing the South Vietnamese government to extend Geneva Prisoner of War Conventions protections to captured Communist guerillas and to establish a system of prisoner of war (POW) camps. Prugh also worked in the civil affairs arena by establishing a rule of law program for advising South Vietnamese attorneys and judges and an advisory program for Vietnamese military legal personnel. Despite these innovations, military justice remained at the forefront of the Army’s experience in Vietnam largely due to the event that became known as the My Lai massacre. Ironically, the case’s aftermath would set the JAG Corps on a new path, far beyond its traditional focus on military justice.

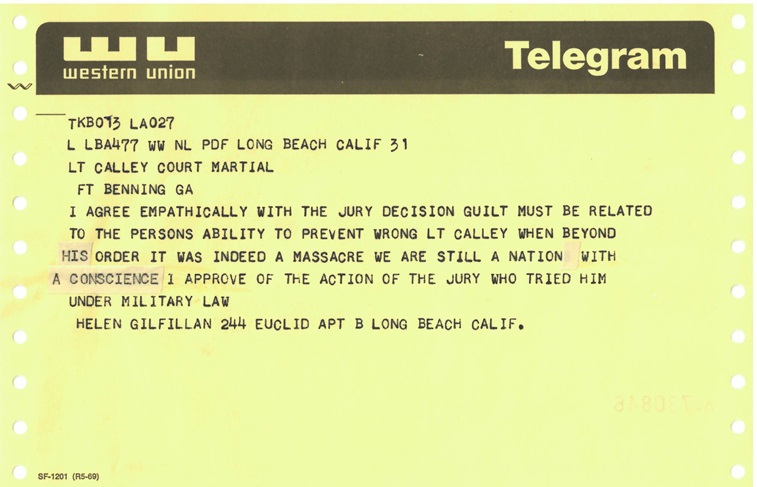

The My Lai Massacre

On March 16, 1968, elements of an American infantry unit murdered several hundred civilians at the South Vietnamese hamlet of My Lai. The incident was covered up until 1969, when reports of the massacre reached Chief of Staff of the Army General William Westmoreland. Thirteen Soldiers, including platoon leader First Lieutenant William L. Calley, were charged with murder. Of the thirteen charged, only Calley was convicted. Calley’s trial received extensive news coverage and became probably the most famous court-martial in American history up to the present day.

Findings and Aftermath

An Army inquiry found that inadequate training in the Law of War had been a factor in the killings at My Lai. In response, the Army revised its regulations in 1970 to require more thorough training on the Hague and Geneva Conventions, with judge advocates and officers with combat experience conducting the training. In 1974, the Department of Defense established a joint Law of War program. The Army JAG Corps was designated as the proponent for its implementation. Crucially, the new directive also required legal review of operational plans.

Operation URGENT FURY

Direct legal support to the planning and execution of operations did not come fully to fruition until the early 1980s. In October 1983, the United States invaded the Caribbean island of Grenada in response to political turmoil in Grenada’s Marxist government, an alleged Communist military buildup on the island, and concerns for the safety of American medical students on the island. The 82nd Airborne Division was the largest Army unit involved in Operation URGENT FURY, and initial plans had the division’s staff judge advocate remaining in the rear while the commander landed on the island with his assault command post (ACP). Hearing of the operation only the day before its commencement, SJA Lieutenant Colonel Quentin Richardson convinced the division chief of staff to include him in the ACP manifest. This decision proved fortuitous. Once on ground in Grenada, the division’s combat operations required a wide variety of legal support. Lieutenant Colonel Richardson and other judge advocates provided legal assistance to Soldiers and families and advised commanders on rules of engagement, detainee operations, damage claims, rules on war trophies, investigation of alleged war crimes, a new status of forces agreement between the United States and Grenada, and other issues. In the aftermath of the Grenada operation, the JAG Corps realized that it had reached a watershed moment in redefining expectations for legal support to the Army. By 1987, operational law (OPLAW) achieved recognition as a core component of the JAG Corps mission and TJAGSA developed an OPLAW curriculum to train Army lawyers in its application.

Operations JUST CAUSE & DESERT STORM

In Operations JUST CAUSE (Panama, 1989) and DESERT SHIELD/DESERT STORM (Persian Gulf, 1990–1991) Army lawyers were fully integrated into Army operational planning and execution. The Persian Gulf conflict required the full gamut of expeditionary legal support, from OPLAW to contracting to military justice. Perhaps most memorably, new “smart” technology and a bombing campaign of several weeks offered ample opportunities for legal input into targeting decisions during DESERT STORM. In the operation’s aftermath, the United States Central Command’s staff judge advocate described DESERT STORM as “the most legalistic war we’ve ever fought.” While the advent of OPLAW had the greatest impact on the JAG Corps’ mission in the post-Vietnam era, the Corps’ structure continued to evolve, and areas of practice continued to expand. The United States Army Legal Services Agency (USALSA), was established in 1973 to provide administrative support for the new Army Judiciary, the appellate counsel divisions, and the Contract Appeals Division. In 1980, the Trial Defense Service was established to provide professionally trained and independent defense counsel services throughout the Army. Additional components added in the 1980s include the Litigation Division, the Intellectual Property Division, the Procurement Fraud Division, and the Environmental Law Division. The U.S. Army Claims Service was activated in 1997.

A New Global Context

With the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991 and the subsequent lack of a major peer adversary, the United States military substantially contracted in size. From 18 divisions and nearly 770,000 personnel in 1989, the Regular Army dropped to 10 divisions and less than 500,000 Soldiers by 1996. At the same time, the Army’s operational tempo accelerated, with 25 contingency operations from 1990–1997, as compared to only 10 contingency operations between 1950 and 1989. The complexity and ambiguity of so-called military operations other than war (MOOTW) served to further imbed Army legal professionals into commanders’ decision-making processes. Stability operations in places like Somalia, Bosnia, and Haiti required extensive legal support. For example, in Somalia in 1992–1993, American and coalition commanders faced a humanitarian disaster and political instability that veered between humanitarian relief operations and active combat. These conditions required the creation of and training on rules of engagement that protected both American Soldiers and local civilians and extensive involvement in civil affairs. Disasters required more traditional humanitarian support, for example during operations SEA ANGEL (Bangladesh, 1991) and PROVIDE COMFORT (Turkey and Iraq, 1991). The Army also became involved in domestic operations, such as the response to the Los Angeles riots and Hurricane Andrew in 1992. Support to civil authorities required careful attention to Posse Comitatus restrictions and rules of engagement, among other issues. In each situation, commanders found that Army legal personnel were essential to enabling effective and lawful operations. This experience arguably prepared the Army well for the conflicts to come in the first decades of the twenty-first century.

21st Century Operations

The terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, set the stage for the Army’s operations up to the present day. Trends of the 1990s, such as confrontations with stateless violent extremist organizations, deepened with the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq that followed. By the 2020s, the Army faced an enduring commitment to the stability operations begun in the 1990s, a continued counterterrorism campaign that was a legacy of 9/11, and a new focus on preparing for large scale combat operations in the face of reemerging peer threats in multiple theaters. To support the Army in these diverse and complex missions, the Army JAG Corps of 2025 has a more highly trained cast of legal professionals from across the Total Army practicing in a wider array of legal fields than in any time in its history. At the operational level, Army legal personnel supported the United States military response in Afghanistan, the Horn of Africa, and other locations beginning in 2001 and in Iraq, Syria, and other Middle Eastern countries after 2003. In Afghanistan alone, more than 500 legal personnel supported operations ENDURING FREEDOM (2001–2014) and FREEDOM’S SENTINEL (2015–2021).

The Global War on Terror

While the history of the Army legal practice in the post-9/11 era requires a full history to grapple with its scale, duration, and complexity, the types of legal support the Army needed had many similarities to the 1990s. The invasion of Iraq in the spring of 2003 featured a brief period of large-scale combat operations, but the Global War on Terror was primarily characterized by a mix of stability and combat operations over the course of long military campaigns. While fighting insurgencies in populated areas, judge advocates provided commanders support in complex targeting decisions and rules of engagement to help achieve operational success. Contingency operations also required support in the areas of intelligence and fiscal law and in detainee operations. Of course, military justice remained central to the JAG Corps mission. Army lawyers handled misconduct and war crimes cases such as the Abu Ghraib prisoner abuse scandal in Iraq. As in Vietnam, Army legal personnel worked with their Afghan and Iraqi colleagues on rule of law programs to bolster the institutional capacity of partner legal systems.

Valor Under Fire

The nature of the fighting in Iraq and Afghanistan also meant that the traditional separation of front lines and rear areas was largely erased. On August 7, 2003, Captain Keith Bracey (who had been wounded in action in May 2003), Warrant Officer One Donnell McIntosh, and other legal personnel from the 1st Armored Division came to the aid of another unit being ambushed by Iraqi insurgents. Helping to evacuate and treat the wounded while under fire, McIntosh became the first legal administrator to be decorated for actions in combat when he was awarded the Bronze Star Medal with Valor device. Captain Bracey, then-Master Sergeant Brian Quarm, and then-Specialist Benjamin Prutz also received the same combat decoration. Tragedy struck the JAG Corps three months later on November 7, 2003, when enemy fire downed a helicopter carrying Regimental Chief Warrant Officer Five Sharon T. Swartworth and Regimental Sergeant Major Cornell W. Gilmore near Tikrit, Iraq, killing both. Since September 11, 2001, a total of six members of the JAG Corps have been killed in action or died in accidents during combat operations. At least 35 others have received Purple Heart awards for combat wounds. Army legal personnel continue to support operations in the Middle East and in theaters of competition and conflict all over the world.

New Era, New Frontiers

While the Army undertook simultaneous overseas contingency operations, it was also undergoing transformation. In the early 2000s, the Army implemented an operational concept that emphasized modularity and flexibility to support small scale contingencies, with brigades allocated more organic combat power. To support the new brigade combat team force structure, judge advocates and a supporting legal team were authorized at the brigade level for the first time. The Army’s reserve component assumed a greater operational role in the wake of the post-Cold War drawdown, a trend that only accelerated after September 11, 2001. While Army Reserve (USAR) and National Guard judge advocates were instrumental in both World Wars, the creation of the U.S. Army Reserve Command in 1990 as a subordinate unit of U.S. Forces Command was an important step in reorienting the reserve component as part of the modern Total Army operational force. In the twenty-first century, USAR and National Guard legal personnel comprise the majority of the JAG Corps’ authorized strength and provide crucial support for both domestic and overseas operations. Civilians have always worked in a variety of capacities alongside and within the JAG Corps, and the civilian workforce experienced significant growth in the twenty-first century. In recognition of their importance to JAG Corps operations, the position of Senior Civilian Attorney was established in 2007. This member of the Senior Executive Service is the primary advisor to TJAG on all matters relating to civilian employees and is charged with the professional development of Judge Advocate Legal Service civilian attorneys.

Preparing for the Future

The Army JAG Corps also updated its training during this period. By the early 2000s, JAG Corps leadership recognized that the branch needed to take better ownership of training and career management for all legal personnel. MOS 27D, Paralegal Specialist, replaced 71D in 2001 to better align training with civilian paralegal standards and to bring all Army legal professionals into Career Management Field 27. In 2003, TJAGSA became The Judge Advocate General’s Legal Center and School (TJAGLCS), added a doctrine and training-focused Legal Center, and aligned the JAG Corps with the Army center of excellence model. The JAG Corps Non-Commissioned Officer Academy (NCOA) was established at TJAGLCS the following year, and Advanced Individual Training moved to Fort Lee, Virginia, in 2012 to take advantage of proximity to the NCOA and its attendant training opportunities. Charlottesville is now truly the Regimental Home for all Army legal personnel.

Military Justice Reform

Military justice has also continued its overall trend toward “civilianization”—bringing military justice into closer alignment with the practices of federal courts – in the past few decades. Following the MJA of 1968, significant developments included the implementation of the Military Rules of Evidence (modeled after the Federal Rules of Evidence) in 1980 and the passage of the Military Justice Act of 1983, which for the first time allowed direct appeal from the Court of Military Appeals to the United States Supreme Court. In 1994, the Court of Military Appeals was renamed the United States Court of Appeals for the Armed Forces (CAAF). Notably in the post-9/11 era, the military faced enormous scrutiny for its handling of sexual harassment and sexual assault as well as other serious crimes. A series of reforms in the National Defense Authorization Acts (NDAAs) between 2016 and 2022 changed the UCMJ and culminated in the establishment in 2023 of a new Office of Special Trial Counsel. The new organization features specially trained prosecutors who have the sole authority to prosecute sexual assault and thirteen other crimes.

Since 1775, the Army’s legal profession has grown and changed significantly. Several trends have characterized the past 250 years: growing complexity in our organization and scope of practice; the continuous evolution of military justice; constant changes to training and education; and the integration of legal support into Army operations at every level. Through all of this change, principled counsel, mastery of the law, stewardship, and servant leadership have remained as constants.

As one considers the legacy of the past 250 years, thoughts about the future inevitably materialize. What will the Army and its JAG Corps look like in 50 years or even another 250 years? While the future is ultimately unknowable, our history helps to chart a consistent path forward: principled counsel, mastery of the law, servant leadership, and stewardship are timeless values and attributes for Army legal professionals. These constants equip the JAG Corps to best serve the Army and the Nation despite inevitable change. In our 250th year, the time has never been better to honor our past and prepare to make our future even better.